Part 1: drinking with number 3.

(This part is mostly backround stuff - I'll be discussing the film properly in the next post.)

The late sixties gave birth to and defined a new cultural archetype: the rock star. There had been rock and roll stars before that, and a hell of a lot of musicians who behaved like rock stars. But in the later part of the sixties, the concept solidified into a distinct look, a distinct lifestyle, and a new mystique and mythology of heroic, life-threatening self-indulgence. The rock star was an archetype woven out of a variety of historical precedents, including the legacies of the Byronic poet/rebel, the bohemian hipster cliques of the Jazz and Beatnik fifties, and the strange cults of the beautiful, youthful corpse that had flourished in Hollywood around figures such as James Dean and Rudolph Valentino. The possibility of premature death is crucial to the mythos of the rock star; there is an air about it that is similar to the Spanish bullfighter, if you replace fighting a bull with living on a day to day basis with an insatiable appetite for whiskey bottles, blow-jobs, and whatever narcotic happens to float its way within arms reach.

The rock star idea embodied a distinct look and attitude. It was a mixture of paradoxes: somewhere between an aristocrat and a thug lay the look that Keith Richards aptly labelled "elegantly wasted." Its sexuality was a paradoxical mixture of surly masculine bravado and androgynous high maintenance, a combination that would have gone, by the time of the hair metal bands of the eighties, into the stratosphere of high camp. Psychedelics imbued the rock star with aspirations towards a kind of mystical or mythic aura, but it was all subsumed into the idea of living perpetually on a precipice, into an adolescent fatalism that is well evoked by the chorus of the Blue Oyster Cult's seventies staple (Don't Fear) The Reaper. It was a very Californian, and more specifically a very Los Angeles phenomenon: a nightside mythology for a town whose wellsprings have always been fame and excess, and the liminal territories where sunny wish-fulfilments become tarnished nightmares.

The rock star idea embodied a distinct look and attitude. It was a mixture of paradoxes: somewhere between an aristocrat and a thug lay the look that Keith Richards aptly labelled "elegantly wasted." Its sexuality was a paradoxical mixture of surly masculine bravado and androgynous high maintenance, a combination that would have gone, by the time of the hair metal bands of the eighties, into the stratosphere of high camp. Psychedelics imbued the rock star with aspirations towards a kind of mystical or mythic aura, but it was all subsumed into the idea of living perpetually on a precipice, into an adolescent fatalism that is well evoked by the chorus of the Blue Oyster Cult's seventies staple (Don't Fear) The Reaper. It was a very Californian, and more specifically a very Los Angeles phenomenon: a nightside mythology for a town whose wellsprings have always been fame and excess, and the liminal territories where sunny wish-fulfilments become tarnished nightmares.If you fed all of these elements into a computer programme, or some kind of Platonic blender, designed to yield up the prototypical rock star, it would probably produce something like Jim Morrison. Morrison grew up as an itinerant military brat, moving with his family from base to base around New Mexico and Southern California. His father was Admiral George Stephen Morrison, who would later command the U.S. Naval forces during the controversial Gulf of Tonkin Incidents which lead to the Vietnam war, making father and son ideal candidates for a zeitgeist-defining Oedipal clash in the latter sixties. As a child, he allegedly witnessed the aftermath of a road accident near an Indian Reservation, an incident Morrison later embellished into a personal mythology of shamanic possession.

In 1965, Morrison washed up on Venice Beach, and quickly gathered about himself a much homelier looking, but virtuosic group of musicians who formed the Doors. Within a year, the band were playing at the legendary Sunset Strip rock club the Whiskey a Go Go. An early instance of Morrison's unpredictable stage theatrics got then fired, but ultimately immortalized in pop culture history. Peaking on an acid trip during their performance of The End, the singer improvised a succinct and mildly obscene summary of the plot of Sophocles' Oedipus Rex. Like fellow tragic youth icon James Dean before him, Morrison had drawn on his own fraught familial experience to articulate a universal generational conflict. And herein lay much of the potency of the Doors, circa America in 1967: at their best they almost unconsciously recast a ubiquitous sense of social upheaval and chaos into the dream logic of myth and apocalypse. According to Lester Bangs' critical but affectionate summary Jim Morrison: Bozo Dionysus a Decade Later: "In the end, perhaps all the moments like these are his real legacy to us, how he took all the dread and fear and even explosions into seeming freedom of the sixties, and made them first seem even more bizarre, dangerous, and apocalyptic than we already thought they were, then turned everything we were taking so seriously into a big joke midstream."

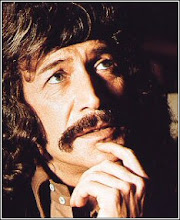

The Doors rapidly became one of the biggest rock groups in America, an unusual cross-over phenomenon that encapsulated both mainstream appeal and something of the darker, underground gravitas of groups like the Velvet Underground. Much of the mass appeal came down to Morrison himself, who had quickly fashioned a template, an image and a persona, that innumerable lead vocalists and poseurs would attempt to tap for generations to come. Physically, Morrison had a remarkably symmetrical, high check-boned visage, framed by a mane of studiously tousled dark hair; it gave him the look of a spoilt, fallen cherub that fitted his Rimbaud/Baudelaire pretensions to perfection. His baritone voice had authority rather than range, and derived its impact more from actorly charisma than musicality. In performance, he lacked most of the basic rudiments of conventional stage-craft, but developed instead an explosive sense of dynamics, a poised, mesmeric slouch before the mike which is now a staple shape in the arsenal of the front man. He was the first of the pioneering rock stars to intuit the true morbid undercurrents of the emerging rock mythos, having provided in The End, When the Music's Over, and Five to One an unintentional preface and commentary on his own eventual demise and canonisation.

The demise, of course, was as swift as the apotheosis. Lester Bangs opined that the band had said everything they had to say on the first record, and were essentially floundering thereafter. This is certainly an overstatement, but once the Doors had fully mined their initial burst of creativity on The Doors and Strange Days, they never again exhibited quite the same degree of purpose and energy. Hunter S. Thompson's "wave speech" from Fear and Loathing eloquently evokes the brilliance and brevity of the sixties counter-culture explosion:

"And that, I think, was the handle - that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn't need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting - on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum - we were riding on the crest of a high and beautiful wave...."

"So now, five years later, you can go out on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark - that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back...."

After '68, the wave for Morrison was palpably in recession. His drinking had by then thoroughly crossed the crucial line separating youthful, romantic abandon and pure, crippling alcoholism. The on-stage theatrics had descended into a boozy, shambolic ghost of their former selves, and the Doors' latter gigs (and their aftermath in the law courts) played out like a farcical redux of the Square Community's long war of attrition against Lenny Bruce earlier in the Sixties. By the end of the decade, it was clear that not everybody was going to make it out at the other end of the first great Renaissance of the rock star. On September 18, 1970, Jimi Hendrix was found dead in a flat in Notting Hill, London; he was followed 16 days later by Janis Joplin. Morrison took to teasing friends that they "were drinking with Number 3." He gained weight, and grew a thick Manson-like beard. The Doors had recorded LA Woman, their last record with Morrison, in large part a bluesy, battle-weary hymn to the City of Lights, when Jim fled with his long-suffering girlfriend Pam to Paris in March 1971, never to return. His Number 3 joke had been uncannily prescient, as his death in Paris rounded off the mystical 27 Club of sixties rock icons who had all crashed along the road of excess at age 27.

After that came endless revivals, and eventually a burgeoning Morrison cult which seems to afflict idealistic young adolescents with a particular intensity. (In 1981, Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugarman published the first Morrison bio No One Here Gets Out Alive, a work of unabashed idolatry that effectively became the gospel of the cult. For many youngsters, No One Here Gets Out Alive became what On the Road had been to Jim himself - a book that was to be absorbed and imitated, a talismanic field-guide on how life itself should be.) The fact that the Morrison mythos doesn't really survive too much sustained adult scrutiny is, to my mind, hardly the point. For a lot of young kids, including myself when I was growing up, Morrison and the Doors operate as a cultural gateway drug par excellence, a significant stepping stone to harder, more substantial substances. The Doors crystallise an incipient tendency in young people towards bohemian, or poetic, or philosophical pursuits, and provide in Jim an icon, an indelible image, to hinge these aspirations and fantasies on.

This kind of iconography, of self-mythologising through the channels of contemporary media, is frequently misunderstood as something shallow or insignificant. In point of fact it remains a very powerful and fascinating cultural currency, a McLuhanesque fusion of medium and message. Personal iconography is an important facet of almost every art-form, but in the realms of movie stardom and popular music, it is virtually the lifeblood. The movie star and the rock star are both entities for whom physicality and personal magnetism are as important a constituent as technical accomplishment. Bob Dylan once said that when he first saw Elvis Presley, he knew that he would never work for anybody, would never have a boss. The reaction was visual - as much as Presley's talent was inspiring, there was also the crucial fact of how he looked, how he carried himself, and how you felt when you saw him. Iconic images have a peculiar power to influence and crystallize our own sense of self, a point expressed eloquently in Patti Smith's recollection of seeing Edie Sedgwick for the first time: "The first time I saw Edie was in Vogue Magazine in 1965. You have to understand where I come from. Living in south Jersey you get connected with the pulse beat of what's going on through magazines.....It was all image.....She was like a thin man in black leotards, white hair and boat-necked sweater. She was such a strong image that I thought, "That's it." It represented everything to me, radiating intelligence, speed, being connected with the moment."

Oliver Stone's 1991 movie The Doors has drawn extensive criticism, both from critics and the surviving Doors, for its larger-than-life, mythologising approach to the Morrison story. Ironically, for a film that is certainly leaden with flaws, this aspect may actually be its greatest strength - an awareness of the degree to which mythology, image-making, and narcissistic fantasies play such an integral rule in what rock music really is, and how it communicates its message to audiences. Similarly, Stone's fetishistic attraction to Morrison's self-destructive habits - few movies have depicted slugging straight from the bottle with such gusto - is a truthful reflection of the fact that rock heroism, like any outlaw mythos, is largely predicated on our ambivalent fascination with reckless excess and self-destruction.

Continued Shortly.

What an excellent post on the backstory to the film - the real story of The Doors and the era that they came into prominence. I also really like how you tied in that great Hunter S. Thompson quote from FEAR & LOATHING IN LAS VEGAS. I hadn't thought of that but now that you mention it, it makes perfect sense.

ReplyDeleteThe Doors, in many respects, really were an embodiment of the spirit of their times, reflecting the darker aspects of that era. And yet, their music is not dated and remains timeless.

I'm really looking forward to your next installment. Great work!

Hey JD, thanks, your kind encouragement is much appreciated! I really enjoyed your take on the movie - I like the way you singled out the scene with Mimi Rogers, which I think is a wonderful depiction of the dark power of fame, how easy it is to get lost in it.

ReplyDeleteAs regards the Doors being timeless, I completely agree. There's loads of great music around now, but if there was ever a time for an apocalptic bard of the unconscious like Jim, it's these crazy days.