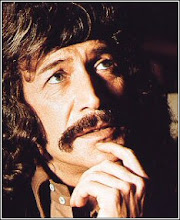

Thief (1981) is Michael Mann’s first theatrical feature. Despite being a very fine film, and featuring easily the most remarkable performance of James Caan’s career, it’s not widely remembered by general audiences today. Viewed from the perspective of Mann’s subsequent work, it seems extraordinarily mature for an opening salvo. Thief tentatively stakes out the primary visual milieu of virtually all the directors subsequent work, which in many respects is the quintessential concern of noir cinema: an exploration of the alternatively seductive and dehumanising characteristics of the nocturnal urban environment. it establishes familiar Mann themes which have been so widely discussed as to barely warrant commentary: its principal conflict is waged between the demands of an extreme form of masculine individualism and commitment to personal vocation, as against those of domesticity, emotional security, and the more stable and integrated spectrum of society. As such, all Mann’s subsequent movies can be viewed as increasingly sophisticated additions and variations on the groundwork established with such unusual clarity of intent with this first outing.

Many critics have tended to place Thief, and its close thematic relative Heat, within a French tradition of psychologically and existentially sophisticated genre cinema, based around the detailed exposition of a central heist and its messy consequences. This is accurate enough, but it is perhaps better to envision Thief as the culmination of a chain of influence which begins in American popular cinema, flourishes in

The next major innovation in the heist movie came via Rififi (1954), a picture made in

The greatest marriage of French and American sensibilities comes in the austere and magisterial work of Jean-Pierre Melville. Both John Woo and Quentin Tarantino have cited Melville as a major influence, though neither seem to have imbibed much of the characteristic restraint and understatement of his movies. Melville regarded classical American cinema with a kind of boyish reverence, and fashioned from its basic mythic archetypes and patterns a uniquely sober and iconic style of genre cinema. The French component in the heist movie, in tandem with how French criticism crystallised the concept of film noir generally, was a question simply of highlighting the elements of deterministic, existential pessimism already intrinsic to the world of the American pulps. Few were perhaps as well-equipped in temperament and background to channel such ideas as Melville. His participation in the Resistance provided him with an indelible, first hand experience of a world of meticulous subterfuge, where divided loyalties, betrayal, and a sense of one’s personal mortality, were all-pervasive realities. Le Cercle Rouge (1970) is the classic French heist movie, outdoing Rififi’s seminal centrepiece for duration, suspense, and sheer methodical detail, and refining the tripartite structure of The Asphalt Jungle into something as unyieldingly formal and precise as an equation; the red circle of the movie’s title seems to refer the action of the film as a tragic, implacable net of causality in which the characters are hopelessly immeshed.

In interviews, Mann tends to downplay the influence of other films on his work, stressing instead the importance of research and a knowledge of the real-life milieu of criminals and law-enforcement agencies. Nevertheless, whether the relationship is intentional or otherwise, the works of Huston, Dassin, and Melville form the natural stylistic and thematic precursors to Thief and Heat, and provide a model for an intellectually weighty variety of crime drama which Mann builds upon.

The other chief pivot of Frank’s character, also developed in prison, is the postcard sized photo collage he has made as a symbolical representation of his dream of a better life. Despite his obvious affinities with the world of criminality, and his obsessive dedication to his craft as a thief, Frank longs for a life of domestic tranquillity and security, and his collage depicts all the trappings of this ideal: wife, children, and leafy suburban house and garden.

Frank’s collage encapsulates what is both sympathetic and unnerving about his character, in that it illustrates the sincerity of his desire for a better life, coupled with an almost sociopathic belief that an idea can be pursued in a single-minded fashion, with no recourse to the complexities and contingencies of real life. A fatal aspect of Frank’s individualism is that he sees the world unfailingly as an extension of his own will, and thus when he sets about attaining his domestic ideal, he does so with almost the same degree of mechanical simplicity with which he has assembled the collage. (I suspect that this must refer, in some oblique fashion, to the tendency of particularly obsessive and driven artists to identify with an aesthetic world over which they have complete control. This point shouldn’t be overstated, but I do think that Mann’s protagonists do represent a romanticised, though certainly not uncritical, exploration of aspects of his own psychology. Federico Fellini had a series of wonderful sets built for La Dolce Vita which emulated real locations in

It is worth noting that as much as Mann’s films deal with characters that identify to a compulsive degree with their vocation or career, the characteristic malaise of a Mann protagonist is actually the longing to escape that vocation. In Manhunter, Will Graham is a brilliant psychological profiler, whose expertise and ability could save literally dozens of lives. However, he has retired, and is reluctant to return to work, because the process of identifying with killers shatters his sanity and sense of selfhood. He really longs to be with his wife and son, a domestic ideal evoked, in quintessential Mann fashion, by lush, cool shades of blue, and the close proximity of the ocean. In Heat, Neil dreams of escaping to

Frank has been dating a down-to-earth waitress named Jessie, and plans to marry her and have children. He has promised that his criminal career will shortly come to an end, believing himself, in the archetypal style of so many sympathetic criminals in noir thrillers, to be a couple of big scores away from retirement. In his haste to actualise this retirement dream, he reluctantly starts working for a gangster called Leo. The chief momentum of the plot kicks in, predicated on Frank simultaneously setting up a big score for Leo, and organising his future life with Jessie. The problem, however, is that Frank’s life, both domestically and professionally, becomes increasingly and inextricably bound up with Leo. When Frank and Jessie are unable to adopt a child, Leo intervenes and provides a mother who is prepared to sell them her child. Meanwhile, Frank discovers that working for Leo has brought him to the attention of the police, who demand a cut of the take from the robbery.

In some respects, Thief could be read as an extreme parable about the struggle between individualism and society. It’s Frank’s desire to lead an ordinary, family-based life which leads to his Mephistophelian pact with Leo, and the beginning of the complete erosion of his status as an independent, self-governing operator. The deal with Leo is a kind of extreme version of a social contract; Frank gets a home and a family, but with them comes a boss, and a fatal entanglement within a corrupt system of bribes and mutual favours; the system, according to both criminals and cops, of “how things are done.” Leo changes from being a kindly and paternal figure to one of pure malevolence, asserting aggressively that he “owns” Frank. Frank, in turn, realizing finally that he cannot achieve his dream on his own terms, falls back on the mental habits he acquired in prison. He dispassionately disassembles his long cherished dream, piece by piece, in an extraordinary eruption of sustained, cathartic violence. He cuts Jessie and their child completely from his life, sets fire to his businesses, and kills Leo. The question remains, however, after Frank has vanished into the dark horizon of the film’s denouncement, to what extent Mann intends Frank’s complete lack of compromise to represent a heroic apotheosis, or the self-defeating actions of a character that is psychologically damaged by his past.

Scored with perhaps the most strident rock music Mann has ever utilised, there is much in Thief’s bravura, Peckinpahesque final shoot-out to suggest the former. A frequent criticism labelled against Mann is that his movies represent a more thoughtful, but nevertheless dated and adolescent fantasy of uncompromising machismo struggling to retain its individualism within a complex, corporate, post-feminist society. To read Thief in this manner, however, is to ignore the nuanced and ambiguous nature of Mann’s protagonists, and the predominant element of tragedy in his work. I have read a number of commentators who have interpreted Frank in Thief and Neil in Heat as figures whose tragedy lies in their temporary deviation from their personal and professional codes. The tragedy, it seems to me, lies more in the codes themselves, which prevent these characters from forming permanent and meaningful attachments, and, ultimately, from being happy. The feminine and the domestic sphere represent a genuine ideal, and a possibility of a saner, happier world, in Mann’s movies. It is part of the particularly noirish ambience of Mann’s cinematic universe that his characters are only very rarely able to attain this ideal. They are heroic, after a fashion, but in more tragic and nuanced fashion. Frank regains a kind of sovereignty at the end of Thief, but he has done so at the cost of destroying a dream which could very well have been salvaged in some fashion, and by first raising, then callously abandoning Jessie’s hopes for a happy future. His actions are at once impressive and sociopathic, both self-assertive and self-defeating. As he strides from Leo’s place into Thief’s abrupt cut to black, he does so into a world which corrodes his soul, and for which he longer possesses an imagery of transcendence or redemption.

Thief is something of a lost gem. Michael Mann has made vastly superior pictures, but he has never written a better script; Thief’s dialogue possesses an absolute knowledge of its milieu, and a brilliant, street-smart lyricism. James Caan has never acted so well; the café sequence with Tuesday Weld has all the rugged, bruised tenderness and poeticism of Marlon Brando’s scenes with Eva Marie Saint in On the Waterfront. He is matched by some brilliant support, particularly from the recently departed Robert Prosky in the role of Leo. For Mann enthusiasts, Thief’s chief fascination lies in the presence of all the thematic, and much of the stylistic, hallmarks of the director’s later work. Mann’s recent experimentation with digital cinematography and increased depth of field urban compositions is prefigured in this debut's preoccupation with capturing the ambience of the nocturnal city at its rawest and most three-dimensional. The themes of Mann’s movies, inextricably bound up as they are with the nocturnal architecture of his visual palette, also begin here.

This is a masterful dissection of a phenomenal film. Can't wait to read the rest of your posts re: Mann's amazing career.

ReplyDeleteGood stuff. Its a pity you won't be looking at The Keep, because its a fascinating, if obviously massively flawed, piece of work.

ReplyDeleteBut I'm looking forward to reading your views on Ali and Miami Vice, which are Mann's most complex and interesting films, for my money.

This was a great, great read. I'm hooked as I think Mann is easily one of America's finest directors. I'm really looking forward to your thoughts on "The Insider" and "Miami Vice".

ReplyDeleteThanks a lot! David, I haven't really seen all of The Keep properly yet, so can't comment on it in too much depth. What I saw was, like you say, quite flawed, but strangely beautiful. Anyway, will hopefully have something on Manhunter next week.

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely fantastic read.

ReplyDeleteGreat article. I couldn't agree more. THIEF has almost become a forgotten film of Mann's but it definitely is one of his strongest and, as you point out, anticipates films like HEAT.

ReplyDeleteGreat article and I look forward to the rest! A lot of Mann's films (especially the "dual protagonist" films) are about The Code vs. Domesticity, and how the two are mutually exclusive. Living by The Code costs Domesticity, whereas achieving Domesticity costs The Code.

ReplyDelete"Heat" - Neil breaks Code near end to avenge buddies, dies. Vincent breaks Code at beginning by having a family, but reconnects with his Code and wins, but loses Domesticity and kills the only person who understands him.

"The Insider" - Wigand breaks The Code before movie starts by making Faustian bargain with Big Tobacco. Reconnects with Code but cost is Domesticity and good job. Bergman has his Code of never burning sources taken away from him by forces beyond his control, returns to Domesticity.

"Collateral" (least thematically satisfying) - Vincent pretends to believe in improvisation but is really into routine, dies. Max pretends to believe in planning but adopts improvisation, thereby abandoning Code and achieving Domesticity.

"Miami Vice" - Code vs. Domesticity for Crockett is obvious, but Tubbs achieves the impossible: by having a woman who also follows Code, he achieves both Code and Domesticity.

Fantastic post. You're an amazing critic.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeletepolo ralph

ReplyDeletemichael kors uk

timberland boots

puma shoes

michael kors outlet

watches for men

polo ralph lauren

sac michael kors

replica watches

new balance soldes

2017.12.26chenlixiang