While he was directing his debut Thief, and later producing Miami Vice and Crime Story for television, Michael Mann conducted on-going and in-depth research into the private and professional lives of law enforcement officers and criminals. As he put it himself: "I like to move through a subculture until I feel the colors and patterns and tones and rhythms of the lives of the people and place." Mann's hands on approach brought experienced operators from both sides of the law into the acting fold: Dennis Farina and John Santucci both had small parts in Thief, and larger roles in Crime Story. Farina had been a Chicago cop for eighteen years, and Santucci a skilled jewel thief. It was within this extended fraternization with the law's enforcers and truants that Mann discovered the genesis for Heat. Chuck Adamson, another veteran police officer, was an old friend of Mann whose experiences on the beat formed much of the template for Crime Story. During the sixties, Adamson had shared a coffee with a thief named McCauley; the pair enjoyed one another's company, despite an acute awareness that an encounter under different circumstances could prove fatal for one of the two men. Later on in '63, Adamson was called to the scene of an armed robbery, and shot McCauley six times.

While he was directing his debut Thief, and later producing Miami Vice and Crime Story for television, Michael Mann conducted on-going and in-depth research into the private and professional lives of law enforcement officers and criminals. As he put it himself: "I like to move through a subculture until I feel the colors and patterns and tones and rhythms of the lives of the people and place." Mann's hands on approach brought experienced operators from both sides of the law into the acting fold: Dennis Farina and John Santucci both had small parts in Thief, and larger roles in Crime Story. Farina had been a Chicago cop for eighteen years, and Santucci a skilled jewel thief. It was within this extended fraternization with the law's enforcers and truants that Mann discovered the genesis for Heat. Chuck Adamson, another veteran police officer, was an old friend of Mann whose experiences on the beat formed much of the template for Crime Story. During the sixties, Adamson had shared a coffee with a thief named McCauley; the pair enjoyed one another's company, despite an acute awareness that an encounter under different circumstances could prove fatal for one of the two men. Later on in '63, Adamson was called to the scene of an armed robbery, and shot McCauley six times.This simple enough anecdote, an insight into the shades of grey that inevitably inhere into even the most adversarial relationships, seemed to haunt Mann, and gradually developed in his mind into what is for many people the quintessential Mann narrative: the story of two lonely, driven men who occupy opposing sides of the law, and who, despite extraordinary differences of character and temperament, recognise in one another both a mutual dependence and an essential similitude. Contrary to the interpretation of Heat frequently espoused by the critic David Thompson, the purpose of this dynamic was by no means to suggest an moral equivalence between the two characters, or even to suggest that they are particularly alike in most respects. Rather, as Mann said himself: "I heard that the detective had some kind of rapport with McCauley, and that was the kernel of the movie. It would be trite to say that they were the flip side of the same coin. McCauley and Hanna share a singularity of intelligence and drivennes, but everything else about their lives is different." Heat was thus about a rapport, an empathy, and a respect between two adversaries, predicated on a shared, perhaps emotionally debilitating commitment to their perspective vocations.

Again, as with Frank in Thief, we can read these characters in variety of ways. They share with Frank the same contradictory mixture of intense self-affirmation and self-abnegation and defeat. We can read them as expressions of the perennial American myth of rugged masculine individualism, transposed onto the complex, impersonal urban architecture of the postmodern world. We can see them as cops and robbers proxies for the experience of the artistic vocation, in a manner which explores the inherent alienation of artists and others who possess a particularly intense absorption in their work, and the close proximity of this absorption to forms of obsessive compulsion and autism. Mann has referred to McCauley as a "highly-organized sociopath", and Hanna as "extremely dysfunctional". Their relationship in Heat is a battle of prowess, a cat and mouse game, and, as Sergio Leone described Once Upon a Time in the West, a long and stately "dance of death."

Mann is known for working slowly and spending a long time in research, but of all his projects, Heat probably had the longest period of gestation. Some form of the script seems to have existed since 1986. In 1989, Mann shot a compressed version of the script in two weeks as the low budget television movie L.A. Takedown; it was a proposed pilot for an NBC series which never materialised. (I can never bring myself to watch L.A. Takedown, since it has been so thoroughly bettered by its later incarnation. The Al Pacino role is played by an actor called Scott Plank, who apparently gives a pretty decent performance, despite possessing the most unfortunate surname imaginable for a thespian.) The precise details of how the script evolved are unknown to me, but by the time it reached the big screen in 1995, Heat had blossomed into arguably Mann's most complex, ambitious, and nuanced script. Working within an elegantly precise three-act structure, Mann had branched out around his two central protagonists, weaving a complex tapestry of secondary characters and domestic sub-plots. While no-one would classify Mann alongside Chekhov as a delineator of psychology, or suggest that his dialogue has quiet the muscular sonorities of a David Mamet, he had nevertheless done a stunning job of fleshing out close to twenty characters, and turning the typical prioritization of genre cinema towards plot mechanics and action on its head. In Mann's script, the characterization, the interaction of the secondary characters, and the languorous, contemplative moments, were as crucial as the action set-pieces, and the final film attains an extraordinary fluidity in the way it moves between alternately romantic, melancholy, and kinetically violent registers.

In its journey from NBC to Hollywood, Heat had also acquired an immense ensemble cast, and orchestrated an unprecedented casting coup: the first together on-screen pairing of Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. The significance of this was two-fold. For movie lovers, De Niro and Pacino were emblematic, iconic figures of the extraordinary creativity and artistic integrity which had characterised the New Hollywood movement of the seventies. American cinema experienced something truly remarkable in that decade, which each successive generation has only served to render more unprecedented, and more worthy of our rueful nostalgia. Establishing themselves in roughly the same years as Nicholson, Hackman, Hoffman, Beatty, and Warren Oates, De Niro and Pacino had nevetheless carved out the greatest niche in the mythos of naturalistic American movie actors since Brando created the template in the fifties.

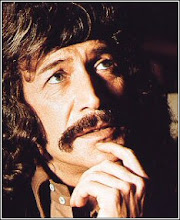

Pacino was a lean, lanky, cherub-faced kid with an air of street-savvy; back then, he was as comfortable with composure and austerity (The Godfather Part 2) as he was with demonstrative physicality (Dog Day Afternoon). De Niro was harder to pin down. In his early years he appeared as a blank slate whose only common denominator was a certain air of purpose and drivenness in performance. He could do a kind of weedy klutziness very well, and also a quality of power, of suppressed ferocity, with an equal faculty. He combined these contradictory qualities as Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, in what remains his most shattering performance. As the seventies passed into the eighties, he had gathered about himself a fearsome legend of obsessive dedication, of physical plasticity and protean disappearance into character. His stock-in-trade, as with the young Brando, became playing volatile, insecure, inarticulate men.

Also, as De Niro and Pacino possessed a special resonance to American cinema in its last truly robust and artistically rigorous period, they had also developed a mythic stature within the crime genre. A fresh-faced Pacino had played a hipster cop fresh out of the academy in Serpico (1973), and laterly the more wizened, world-weary variety in Sea of Love (1989). On the other side of the law, he had played Brian de Palma's cartoonish Cuban ubermench Tony Montana in Scarface, and his older, more contemplative and soulful Hispanic cousin in the same director's Carlito's Way. De Niro, unlike the majority of major American movie stars, tended to steer towards flawed, if not pungently unpleasant characters, and thus spent most of his time on the wrong side of the law. In the seventies, his star took flight as the small-time hoodlum and eternal hustler Johnny Boy in Mean Streets; he played a virile, brill-creamed Vito Corleone for Coppola, a paunchy, petulant Al Capone for de Palma, and also took the lead in Scorsese's nineties crime epics Goodfellas and Casino.

For these reasons, it was particularly apt that these two actors should embody Mann's battle of prowess between two aging, obsessive, and preeminent professionals. It added a charge to the eventual encounter in the diner which had a rich resonance outside the drama of the movie. As their characters circle around one throughout Heat, De Niro and Pacino had hovered about one another for years, both in terms of professional stature, and iconic roles in American cops and robbers movies. The eighties and the nineties were to a large degree a twilight of the idols for the seventies auteurs. When De Niro and Pacino made Heat, their titanic stature was still more or less intact, but both, also, were on the slide: Pacino into exaggerated self-parody and the unfortunate status of an in-joke, and De Niro into a perhaps more lamentable condition of sheer disinterest. The sly sparring and defiant expressions of dedication to vocation expressed in the diner scene are thus both "a mythic moment", as David Denby asserted, and a sad reminder of the many years yet to come between these great actors and the height of their prowess.

To be concluded shortly.

To be concluded shortly.