Harold “Herk” Harvey made only one feature film in his lifetime, and Carnival of Souls (1962) may constitute one of the most tragically short-lived American directorial careers this side of Charles Laughton. By now a thoroughly discovered “lost gem”, Carnival followed a fairly archetypal trajectory for a future cult film: shot in just three weeks for an estimated $33,000, it disappeared without a trace on its initial release, and gradually found its audience via late night television and the burgeoning midnight movie circuit of the 70’s. In 1989, it received a limited run in art-house cinemas, and in 2000 this once forgotten drive-in curio gained the ultimate stamp of legitimacy: a lavish release on DVD on the Criterion Collection label. Though shorn of some of its obscurity, Carnival of Souls is nevertheless one of those rare films which will always feel like a personal discovery. It possesses the requisite mix of kitsch, artiness, and other-worldly strangeness that makes a true cult film.

Defining cult cinema is an exercise to which you could devote an inordinate amount of time, without attaining anything substantial or conclusive. The reason for this is plain enough: a cult film can be any type of movie that engenders a particularly zealous and devoted following. In this regard, cult doesn’t correspond to any particular genre or overriding aesthetic. The idea that a cult phenomenon comes from somewhere outside of the mainstream, or must experience an initial period of disparagement or obscurity, is no longer really a necessary prerequisite. Comic-book blockbusters like the Dark Knight are an example of cinema that possesses within its massive mainstream audience a smaller faction for whom the movie is a cult phenomenon. Similarly, television shows like Lost illustrate the degree to which smart popular entertainments can adroitly cater to both more casual and cultish audiences.

Outside of a strictly literal interpretation of the term, however, cult cinema has a specific ambience and aesthetic, albeit one which remains broad and difficult to define. In many respects, it is legitimately an outsider art-form, which venerates the wilfully individual and the grandiosely eccentric. Cult cinema flourished in genres that fell outside the pale of critical respectability, and derived much of its allure from the idea of discovering hidden gems and sheer oddities out at the fringes of culture. In so far as cult cinema is associated with kitsch, it is less concerned with a simple-minded so-bad-its-good aesthetic, and more with films which somehow manage to completely evade such normally firm qualitative distinctions.

Stemming from all these factors, the most salient characteristic of cult cinema is probably an inherent resistance to easy categorization. The best cult films blur the distinction between aspects of cinema which tend to be placed at the furthest remove from one another: between art and exploitation, and critically canonical notions of good taste and bad. This is a characteristic which is common to many great cult film-makers, including David Lynch, Dario Argento, and Seijun Suzuki; it is also to be found in spades in Carnival of Souls, a richly atmospheric and evocative B-movie described by Bruce Kawin as “an episode of the Twilight Zone directed by Ed Wood and Antonioni.”

Herk Harvey was born in Windsor, Colorado in 1925. He served in the US Navy during World War 11, and briefly studied chemical engineering before a passion for acting brought him to the University of Kansas in 1945 to study theatre. Long before he directed Carnival, Harvey was involved with a cinematic sub-genre which would itself become a staple for cult/kitsch enthusiasts of the future: the educational and industrial film industry of the forties and fifties.

After World War 11, America witnessed a massive boom in the production of short, instructive documentary-dramas which dealt with a variety of issues, particularly health, safety, social development, and sociological problems. Unintentionally stilted and melodramatic, these industrial/educational films reflect a prosperous society of many contradictions: one which simultaneously venerated suburban conformity, and dreaded the uniformity of communism; that fetishized youth and independence, and struggled against juvenile delinquency and beatnik unrest. To the post-sixties, post-Watergate culture, these “mental hygiene” shorts became comic, illuminating icons of a vanished age and value-system.

The Midwest was the Hollywood of industrial film-making, with Coronet in Chicago, Calvin Company in Kansas City, and the Centron Corporation in Lawrence, KS. Beginning in 1947 with a one reel sewing lesson called Sowing Simple Seams, the Centron Corporation gradually became a giant in the field, memorably lifting the lid on bullies, gossip queens, racial prejudice, and venereal disease. Herk Harvey started out as one of the many Lawrence locals who acted for Centron, gradually becoming a producer and director for the company. Here is “What About Juvenile Delinquency?”, which Harvey directed for Centron in 1954:

One day, Harvey was driving home to Lawrence from Los Angeles when he noticed the ruins of the old Saltair Pavilion on the southern shore of the Great Salt Lake. In existence in a variety of forms since 1893, the Saltair had been conceived by local Mormon and business interests as a pious, family-orientated western equivalent to Coney Island. In 1925 it also acquired a massive dance hall, but a variety of disasters including two major fires and the recession of the lake water, coupled with the gradual emergence of new leisure activities such as movie theatres, drive-ins, and television lead to the Pavilion’s closure in 1958. Struck by the eerie ambience and rotting grandeur of the old Pavilion, Harvey was inspired to make a film “about dead people dancing in a ballroom on the Great Salt Lake.” With this simple image as his proviso, Harvey enlisted best friend John Clifford to write a script, and Carnival of Souls was born.

As well being an engrossing Gothic or supernatural mystery, Carnival is a fairly intense study of alienation, psychological detachment, and madness. It begins very abruptly, with two groups of young people engaged in the perennial fifties activity of drag-racing. The cars collide on a bridge, and one of them hurtles into the river. The title sequence establishes immediately that Carnival possesses an artistic sensibility that belies its non-professional acting and lo-fi production values: the slanting credits are sharply placed over atmospheric close shots of the river’s banks and eddying waters. One of the girls from the car, Mary Henry, emerges later on the shore in a distracted state, unable to remember how she survived the crash. Henry is somewhat overplayed by Lee Strasburg graduate Candace Hiligoss, who never really registered anywhere else on the cinematic radar. Nevertheless, her physicality is compulsively watchable, and perfect for the role; her large, oval features remind many viewers of fellow ghoul victim Barbara (Judith O’Dea) in Romero’s later Night of the Living Dead, and others of Tipi Hedren in Hitchcock’s zombie of the diminutive, feathered variety classic The Birds.

From the outset, Mary’s coldness and detachment is emphasized: she is pictured playing the organ at a factory, dwarfed by its immense and baroque structure. Later the supervisor tells her that she plays intelligently, but without any real soul or feeling. This fundamental dislocation from life is the keynote for Mary’s character throughout the film, and it is left to the audience to decide whether this is as a result of the crash, or simply her disposition all along; whether, in other words, the plot is supernatural in orientation, or hallucinatory and psychological in essence. As Mary travels to Salt Lake City to work as a church organist, the totality of her estrangement is gradually revealed. She becomes the object of neighbouring boarder Mr. Linden (Sydney Berger)’s tenacious and boorishly articulated lust. Linden is a boozy storeroom worker whose appearance somehow suggests a Pee Wee Herman with Marlon Brando’s burly and insinuating physique. While her coldness towards him is understandable, she later reveals to the town doctor that she has never had a relationship with a man, nor feels any inclination towards physical intimacy.

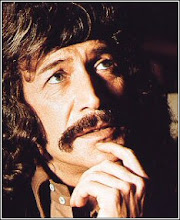

Clifford’s quite intelligent and compressed script also asserts that Mary is as estranged from the spiritual dimension of life as the physical. She regards her work in the church simply as a job, an attitude which seems to unsettle the simple-minded Mr. Linden. Mary’s chief preoccupation in the film is the same as that of the audience: to try to understand herself, and why she is so different. She is pursued by a sardonically grinning ghoul called simply the Man, who is very redolent of something from David Lynch’s feverish imagination. (The Man is played by Herc Harvey himself.) Having seen the Saltair Pavilion on her way to the city, she becomes convinced that it has some kind of profound significance to her condition. The audience, however, like the town doctor, is left to wonder how much of this is only in her imagination.

Though Carnival ultimately resolves itself with a supernatural explanation, in many respects Harvey and Clifford utilise supernatural conventions to explore extreme states of loneliness, alienation, and mental instability. The movie forces us to experience the world completely through Mary’s perspective. In this sense, it reminds me quite a lot of Polanski’s Repulsion; both movies plunge the viewer into an unsettling, hallucinatory, and subjective space, and feature similar underlying themes of sexual neurosis and loneliness. In Carnival’s most remarkable and dreamlike sequences, Mary becomes literally invisible to the other townspeople around her. Harvey cuts out all the sound, with the exception of Mary’s heightened footsteps. As in the common sensation reported by schizophrenics and manic depressives, Mary looks at the world as though through a barrier, with no ultimate connection to it. The everyday world of shop-keepers, families, and policemen move silently and obliviously about, in a stunning tableau that evokes a marriage of Norman Rockwell, Jean Cocteau, and Edvard Munch. In these scenes, Harvey achieves a striking subversion of the educational/industrial film, whose ambience flows into Carnival. The “mental hygiene” movies were completely entrenched in an ideology of the normative; they venerated an ideal of cohesive community and conformity, and presented the outsider in a light of lurid, sensationalistic abnegation. Carnival forces the viewer into the perspective of the outsider, consequently imbuing the community, and the daylight world of the ordinary and normative, with an air of dreamlike menace not seen again until the works of David Lynch. Harvey achieved extraordinary things with the limited resources available to him, and revealed an innate gift for atmosphere and imagery. Sadly his talent was never developed further, but Carnival’s bold mixture of art and schlock would prove widely influential in the subsequent explosion of cult/midnight movies.